Why Is There No Dna Reading for Me

The False Promise of Dna Testing

The forensic technique is becoming ever more than common—and e'er less reliable.

One evening in November of 2002, Ballad Batie was sitting on her living-room couch in Houston, flipping through channels on the television, when she happened to catch a teaser for an upcoming news segment on KHOU xi, the local CBS affiliate. She leapt to her anxiety. "I scared the kids, I was screaming so loud," Batie told me recently. "I said, 'Thank y'all, God!' I knew that all these years afterwards, my prayers had been answered."

The subject of the segment was the Houston Constabulary Department Crime Laboratory, amid the largest public forensic centers in Texas. By one estimate, the lab handled Deoxyribonucleic acid evidence from at least 500 cases a year—mostly rapes and murders, simply occasionally burglaries and armed robberies. Interim on a tip from a whistle-blower, KHOU 11 had obtained dozens of Dna profiles processed by the lab and sent them to independent experts for assay. The results, William Thompson, an chaser and a criminology professor at the University of California at Irvine, told a KHOU xi reporter, were terrifying: It appeared that Houston police technicians were routinely misinterpreting even the most bones samples.

"If this is incompetence, it's gross incompetence … and repeated gross incompetence," Thompson said. "You have to wonder if [the techs] could actually exist that stupid."

Carol Batie watched the entire segment, rapt. Every bit shortly as it ended, she e-mailed KHOU eleven. "My son is named Josiah Sutton," she began, "and he has been falsely defendant of a crime." Four years earlier, Batie explained, Josiah, then 16, and his neighbor Gregory Adams, 19, had been arrested for the rape of a 41-year-old Houston woman, who told constabulary that two young men had abducted her from the parking lot of her apartment complex and taken turns assaulting her every bit they drove effectually the metropolis in her Ford Expedition.

A few days afterward reporting the law-breaking, the adult female spotted Sutton and Adams walking down a street in southwest Houston. She flagged down a passing patrol car and told the officers within that she had seen her rapists. Police detained the boys and brought them to a nearby station for questioning. From the beginning, Sutton and Adams denied any involvement. They both had alibis, and neither of them matched the profile from the victim's original account: She'd described her assailants as short and skinny. Adams was 5 human foot 11 and 180 pounds. Sutton was 3 inches taller and 25 pounds heavier, the captain of his high-school football squad.

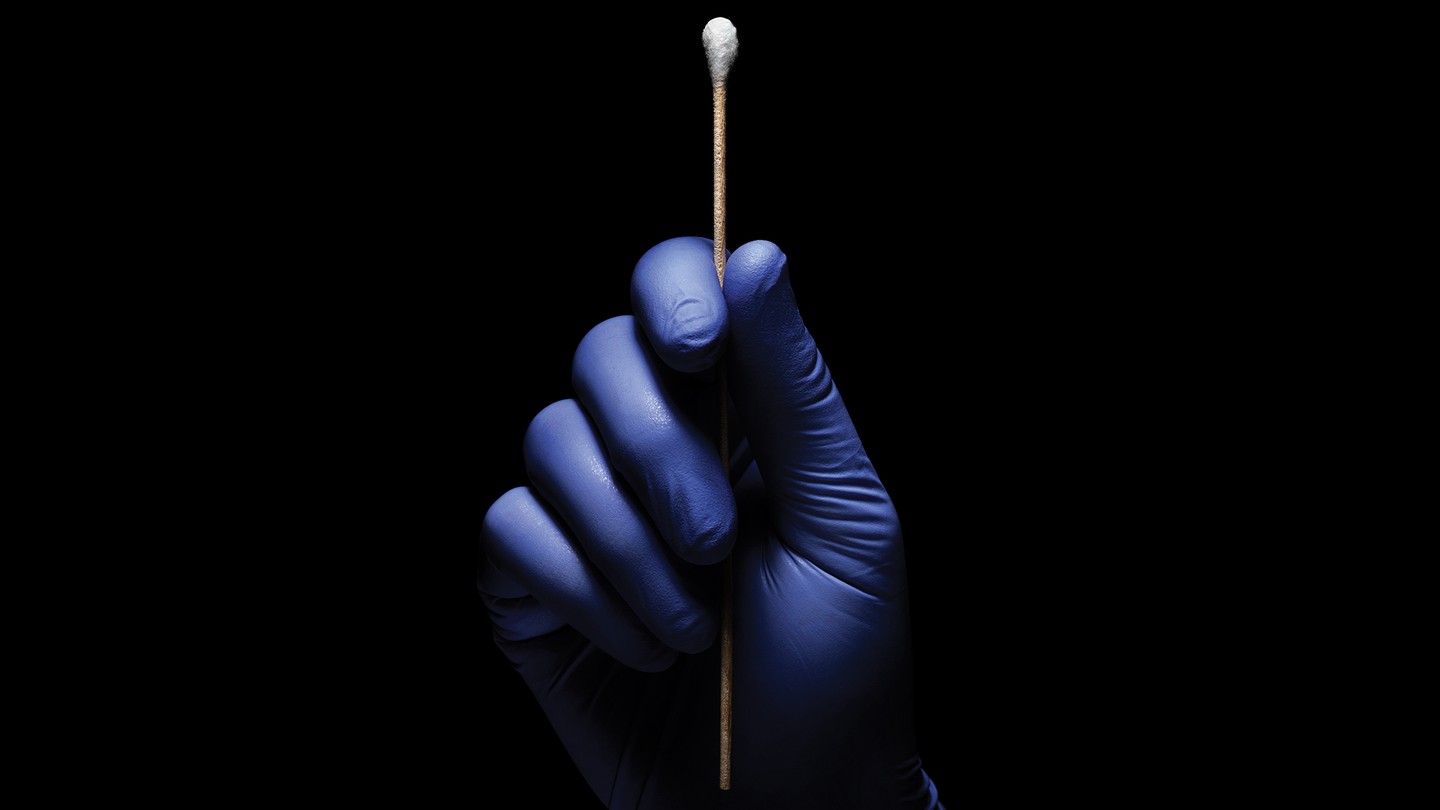

The Dna evidence was harder to refute. Having seen enough prime-time Goggle box to believe that a DNA test would vindicate them, Sutton and Adams had agreed, while in custody, to provide the law with blood samples. The blood had been sent to the Houston criminal offence lab, where an analyst named Christy Kim extracted and amplified DNA from the samples until the distinct genetic markers that swim in every human cell were visible, on exam strips, as a staggered line of bluish dots.

Kim then compared those results with DNA obtained from the victim's torso and clothing and from a semen stain found in the back of the Expedition. A vaginal swab independent a complex mixture of genetic material from at least three contributors, including the victim herself. Kim had to determine whether Sutton'southward or Adams's genetic markers could be plant anywhere in the pattern of dots. Her report, delivered to police and prosecutors, didn't implicate Adams, but concluded that Sutton'south Deoxyribonucleic acid was "consistent" with the mixture from the vaginal swab.

In 1999, a jury establish Sutton guilty of aggravated kidnapping and sexual assail. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison. "I knew Josiah was innocent," Batie told me. "Knew in my eye. But what could I do?" She wrote to the governor and to state representatives, but no 1 proved willing to assist. She also wrote to lawyers at the Innocence Project in New York, who told her that, as a dominion, they didn't take cases where a definitive DNA lucifer had been established.

Batie was starting to think her son would never be freed. Only the KHOU xi segment, the offset of a multipart investigative series on the Houston crime lab, encouraged her. Shortly after eastward‑mailing the station, she received a call from David Raziq, a veteran television producer in charge of KHOU 11's investigative unit. In the course of their work on the series, Raziq and his squad had uncovered a couple of close calls with wrongful conviction—in one case, a human had been falsely accused, on the basis of improperly analyzed DNA show, of raping his stepdaughter. But in those instances, attorneys had managed to demonstrate the problems earlier their clients were sent to prison.

Batie manus-delivered the files from her son'south example to Raziq, who forwarded them on to William Thompson, the UC Irvine professor. Thompson had been studying forensic science for decades. He'd begun writing about DNA testify from a critical perspective in the mid-1980s, as a doctoral candidate at Stanford, and had staked out what he describes as a "solitary" position every bit a forensic-Deoxyribonucleic acid skeptic. "The technology had been accepted by the public equally a argent bullet," Thompson told me this wintertime. "I happened to believe that information technology wasn't."

Together with his wife, also an chaser, Thompson unpacked the two boxes containing the files from Sutton's trial and spread them out beyond their kitchen table. His wife took the transcripts, and Thompson took the DNA tests. Almost immediately, he found an obvious fault: In creating a Deoxyribonucleic acid profile for the victim, Kim had typed three separate samples, two from claret and another from saliva. The resulting Dna profiles, which should accept been identical, varied essentially. This solitary was cause for serious concern—if the tech couldn't exist trusted to go a consistent Deoxyribonucleic acid profile from a unmarried person, how could she exist expected to brand sense of a complex mixture like the ane from the vaginal swab?

Much more lamentable were Kim's conclusions about the criminal offence-scene evidence. Examining photocopies of the test strips, Thompson saw that Kim had failed to reckon with the fact that Sutton's DNA didn't match the semen sample from the backseat of the Trek. If the semen came from 1 of the attackers—as was almost sure, based on the victim's business relationship—then Kim should have been able to subtract those genetic markers, forth with the victim'due south own, from the vaginal-swab mixture. The markers that remained did non match Sutton's profile.

"It was exculpatory prove," Thompson told me. "And the jury never heard information technology."

KHOU xi flew a reporter out to Irvine and taped a new interview with Thompson. Sutton's case was taken up by Robert Wicoff, a defence force attorney in Houston, who persuaded a Texas approximate to have the Deoxyribonucleic acid bear witness reprocessed past a private testing facility. As Thompson had predicted, the results confirmed that Sutton was not a friction match. In the spring of 2003, more than than four years after his abort, Sutton was released from prison. His mother was waiting for him at the gates, her eyes brilliant with tears. "Going to prison, for me, was similar seeing my decease earlier it happens," Sutton later told a local newspaper reporter.

In 2006, a cold hit in the FBI's Combined Dna Alphabetize Arrangement, or codis, would lead police force to Donnie Lamon Immature, a convicted felon. Immature confessed that in 1998, he and an accomplice had raped a Houston adult female in her Ford Trek. In January 2007, Young pleaded guilty to the crime.

Christy Kim was fired from the Houston crime lab, merely reinstated later her lawyer argued that her errors—which ranged from how she had separated out the complex mixture to how she had reported the odds of a random match—were a product of systemic failures that included inadequate supervision. (Kim could non exist reached for comment.) Sutton's case became one of the central pillars of a public enquiry into practices at the lab. "The system failed at multiple points," the caput of the research, Michael Bromwich, concluded.

Thompson was gratified by the overturning of Sutton's conviction: The dangers he'd been warning about were obviously real. "For me, there was a shift of emphasis after Josiah," Thompson told me. "It was no longer a question of whether errors are possible. Information technology was a question of how many, and what exactly we're going to exercise about it." Simply as technological advances have fabricated Dna bear witness at once more trusted and farther-reaching, the answer has only become more than elusive.

1000odern forensic science is in the midst of a great reckoning. Since a serial of high-profile legal challenges in the 1990s increased scrutiny of forensic bear witness, a range of long-standing crime-lab methods have been deflated or outright debunked. Seize with teeth-mark analysis—a kind of dental fingerprinting that dates back to the Salem witch trials—is now widely considered unreliable; the "uniqueness and reproducibility" of ballistics testing has been chosen into question by the National Research Quango. In 2004, the FBI was forced to issue an amends afterwards it incorrectly continued an Oregon attorney named Brandon Mayfield to that bound's train bombings in Madrid, on the footing of a "100 pct" lucifer to partial fingerprints constitute on plastic numberless containing detonator devices. Terminal year, the bureau admitted that it had reviewed testimony by its microscopic-pilus-comparison analysts and found errors in at to the lowest degree 90 percent of the cases. A thorough investigation is now under way.

DNA typing has long been held up as the exception to the dominion—an infallible technique rooted in unassailable science. Different most other forensic techniques, developed or commissioned by law departments, this one arose from an bookish discipline, and has been studied and validated past researchers around the world. The method was pioneered past a British geneticist named Alec Jeffreys, who stumbled onto it in the autumn of 1984, in the class of his research on genetic sequencing, and soon put it to utilise in the field, helping police force crack a pair of previously unsolved murders in the British Midlands. That instance, and Jeffreys's invention, made front-folio news around the earth. "It was said that Dr. Alec Jeffreys had done a disservice to crime writers the world over, whose stories oftentimes eye around doubtful identity and uncertain parentage," the old detective Joseph Wambaugh wrote in The Blooding, his book on the Midlands murders.

A new era of forensics was being ushered in, one based not on intrinsically imperfect intuition or inherently subjective techniques that seemed like science, but on human genetics. Several private companies in the U.S. and the U.Thou., sensing a commercial opportunity, opened their own forensic-DNA labs. "Conclusive results in only one test!" read an advertisement for Cellmark Diagnostics, one of the outset companies to market DNA-typing technology stateside. "That's all it takes."

As Jay Aronson, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, notes in Genetic Witness, his history of what came to be known every bit the "DNA wars," the applied science's introduction to the American legal system was by no means smooth. Defence force attorneys protested that Dna typing did non pass the Frye Test, a legal standard that requires scientific prove to accept earned widespread acceptance in its field; many prominent academics complained that testing firms were not existence adequately transparent about their techniques. And in 1995, during the murder trial of O. J. Simpson, members of his so-chosen Dream Team famously used the specter of Dna-sample contamination—at the point of collection, and in the crime lab—to invalidate evidence linking Simpson to the crimes.

But gradually, testing standards improved. Crime labs pledged a new degree of thoroughness and discipline, with added training for their employees. Analysts got better at guarding against contamination. Extraction techniques were refined. The FBI created its codis database for storing Deoxyribonucleic acid profiles of convicted criminals and arrestees, along with an accreditation process for contributing laboratories, in an attempt to standardize how samples were nerveless and stored. "There was a sense," Aronson told me recently, "that the problems raised in the Deoxyribonucleic acid wars had been satisfactorily addressed. And a lot of people were gear up to motility on."

Among them were Dream Team members Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld, who had founded the Innocence Projection in 1992. Now convinced that Deoxyribonucleic acid analysis, provided the bear witness was collected cleanly, could expose the racism and prejudice endemic to the criminal-justice system, the ii attorneys set most applying it to dozens of questionable felony convictions. They take since won 178 exonerations using DNA testing; in the majority of the cases, the wrongfully convicted were blackness. "Defense lawyers slumber. Prosecutors prevarication. Dna testing is to justice what the telescope is for the stars … a way to come across things every bit they actually are," Scheck and Neufeld wrote in a 2000 book, Actual Innocence, co-authored by the announcer Jim Dwyer.

While helping to overturn wrongful convictions, DNA was as well condign more integral to establishing guilt. The number of state and local crime labs started to multiply, as did the number of cases involving DNA show. In 2000, the year afterwards Sutton was convicted, the FBI'due south database contained fewer than 500,000 Dna profiles, and had aided in some i,600 criminal investigations in its first two years of being. The database has since grown to include more 15 million profiles, which contributed to tens of thousands of investigations final year alone.

Every bit recognition of DNA's revelatory power seeped into pop culture, courtroom experts started talking well-nigh a "CSI effect," whereby juries, schooled by television law procedurals, needed only to hear those three magic messages—Deoxyribonucleic acid—to make it at a guilty verdict. In 2008, Donald East. Shelton, a felony trial guess in Michigan, published a written report in which one,027 randomly summoned jurors in the city of Ann Arbor were polled on what they expected prosecutors to present during a criminal trial. 3-quarters of the jurors said they expected Deoxyribonucleic acid prove in rape cases, and almost half said they expected information technology in murder or attempted-murder cases; 22 pct said they expected Deoxyribonucleic acid prove in every criminal instance. Shelton quotes one district attorney as saying, "They expect us to have the virtually avant-garde technology possible, and they expect it to look similar it does on television."

Shelton institute that jurors' expectations had little effect on their willingness to captive, just other research has shown DNA to be a powerful propellant in the courtroom. A researcher in Commonwealth of australia recently found that sexual-assault cases involving DNA evidence in that location were twice equally likely to accomplish trial and 33 times every bit likely to effect in a guilty verdict; homicide cases were 14 times as likely to reach trial and 23 times as likely to terminate in a guilty verdict. Every bit the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, in the United Kingdom, pointed out in a major study on forensic evidence, even the knowledge that the prosecution intends to innovate a DNA match could be enough to get a defendant to capitulate.

"You reached a bespeak where the questions about collection and analysis and storage had largely stopped," says Bicka Barlow, an attorney in San Francisco who has been handling cases involving Deoxyribonucleic acid testify for two decades. "DNA evidence was entrenched. And in a lot of situations, for a lot of lawyers, it was at present too plush and time-intensive to fight."

DNA analysis has risen above all other forensic techniques for good reason: "No [other] forensic method has been rigorously shown able to consistently, and with a high degree of certainty, demonstrate a connexion between show and a specific private or source," the National Research Council wrote in an influential 2009 report calling out inadequate methods and stating the need for stricter standards throughout the forensic sciences.

The problem, as a growing number of academics see information technology, is that science is merely as reliable as the manner in which we use it—and in the case of DNA, the mode in which we utilise information technology is evolving rapidly. Consider the following hypothetical scenario: Detectives detect a pool of blood on the floor of an apartment where a man has just been murdered. A technician, following proper anticontamination protocol, takes the blood to the local crime lab for processing. Claret-typing shows that the sample did not come from the victim; most likely, information technology belongs to the perpetrator. A day later, the detectives arrest a doubtable. The suspect agrees to provide blood for testing. A pair of well-trained crime-lab analysts, double-checking each other's work, establish a match between the two samples. The detectives can now place the suspect at the scene of the crime.

When Alec Jeffreys devised his DNA-typing technique, in the mid-1980s, this was as far equally the scientific discipline extended: side-past-side comparison tests. Sizable sample against sizable sample. The state of engineering at the time mandated it—y'all couldn't test the DNA unless y'all had plenty of biological textile (blood, semen, mucus) to work with.

But today, near large labs accept access to cutting-edge extraction kits capable of obtaining usable Dna from the smallest of samples, like then-chosen bear upon Deoxyribonucleic acid (a smeared thumbprint on a window or a speck of spit invisible to the heart), and of identifying individual DNA profiles in complex mixtures, which include genetic cloth from multiple contributors, every bit was the case with the vaginal swab in the Sutton case.

These advances take greatly expanded the universe of forensic evidence. But they've besides made the forensic analyst's task more than difficult. To empathise how circuitous mixtures are analyzed—and how easily those analyses can get wrong—information technology may exist helpful to recall a footling scrap of high-school biological science: We share 99.nine percent of our genes with every other human on the planet. However, in specific locations along each strand of our DNA, the genetic code repeats itself in ways that vary from one individual to the next. Each of those variations, or alleles, is shared with a relatively pocket-sized portion of the global population. The best way to determine whether a drib of blood belongs to a serial killer or to the president of the United States is to compare alleles at as many locations every bit possible.

Think of it this fashion: There are many thousands of paintings with blue backgrounds, but fewer with blue backgrounds and yellow flowers, and fewer still with blueish backgrounds, yellow flowers, and a mounted knight in the foreground. When a forensic analyst compares alleles at 13 locations—the standard for most labs—the odds of 2 unrelated people matching at all of them are less than ane in ane billion.

With mixtures, the math gets a lot more than complicated: The number of alleles in a sample doubles in the case of ii contributors, and triples in the case of three. Now, rather than a painting, the Dna profile is similar a stack of transparency films. The analyst must determine how many contributors are involved, and which alleles vest to whom. If the sample is very small or degraded—the two often go hand in hand—alleles might drop out in some locations, or appear to exist where they exercise not. Of a sudden, we are dealing not so much with an objective science as an interpretive art.

A groundbreaking study by Itiel Dror, a cognitive neuroscientist at Academy College London, and Greg Hampikian, a biology and criminal-justice professor at Boise Country University, illustrates exactly how subjective the reading of complex mixtures can be. In 2010, Dror and Hampikian obtained paperwork from a 2002 Georgia rape trial that hinged on Deoxyribonucleic acid typing: The chief bear witness implicating the defendant was the accusation of a co-defendant who was testifying in exchange for a reduced sentence. Two forensic scientists had concluded that the defendant could not be excluded as a correspondent to the mixture of sperm from within the victim, meaning his Deoxyribonucleic acid was a possible match; the defendant was constitute guilty.

Dror and Hampikian gave the DNA evidence to 17 lab technicians for examination, withholding context nigh the instance to ensure unbiased results. All of the techs were experienced, with an average of nine years in the field. Dror and Hampikian asked them to determine whether the mixture included Dna from the accused.

In 2011, the results of the experiment were fabricated public: Merely i of the 17 lab technicians concurred that the accused could not be excluded equally a contributor. Twelve told Dror and Hampikian that the Deoxyribonucleic acid was exclusionary, and four said that information technology was inconclusive. In other words, had any one of those xvi scientists been responsible for the original DNA analysis, the rape trial could have played out in a radically different way. Toward the end of the written report, Dror and Hampikian quote the early Deoxyribonucleic acid-testing pioneer Peter Gill, who once noted, "If yous show 10 colleagues a mixture, you will probably end upwards with 10 dissimilar answers" as to the identity of the contributor. (The study findings are at present at the heart of the defendant's motion for a new trial.)

"Ironically, you accept a technology that was meant to help eliminate subjectivity in forensics," Erin Murphy, a law professor at NYU, told me recently. "But when you first to drill down deeper into the way crime laboratories operate today, yous encounter that the subjectivity is still there: Standards vary, grooming levels vary, quality varies."

Concluding year, Potato published a book called Inside the Prison cell: The Night Side of Forensic Deoxyribonucleic acid, which recounts dozens of cases of Dna typing gone terribly wrong. Some veer close to farce, such every bit the 15-twelvemonth hunt for the Phantom of Heilbronn, whose DNA had been plant at more than 40 criminal offense scenes in Europe in the 1990s and early 2000s. The DNA in question turned out to belong not to a serial killer, but to an Austrian factory worker who fabricated testing swabs used by police force throughout the region. And some are tragic, similar the tale of Dwayne Jackson, an African American teenager who pleaded guilty to robbery in 2003 later being presented with damning DNA evidence, and was exonerated years later, in 2011, afterward a law department in Nevada admitted that its lab had accidentally swapped Jackson's DNA with the real culprit's.

Most troubling, Murphy details how quickly fifty-fifty a trace of DNA tin now become the foundation of a case. In 2012, police in California arrested Lukis Anderson, a homeless man with a rap canvas of nonviolent crimes, on charges of murdering the millionaire Raveesh Kumra at his mansion in the foothills exterior San Jose. The case against Anderson started when law matched biological matter found under Kumra's fingernails to Anderson's DNA in a database. Anderson was held in jail for v months before his lawyer was able to produce records showing that Anderson had been in detox at a local infirmary at the time of the killing; information technology turned out that the same paramedics who responded to the distress call from Kumra'due south mansion had treated Anderson earlier that night, and inadvertently transferred his DNA to the crime scene via an oxygen-monitoring device placed on Kumra's hand.

To Murphy, Anderson's case demonstrates a formidable problem. Contagion is an obvious hazard when it comes to Deoxyribonucleic acid analysis. Merely at least contamination can be prevented with care and proper technique. DNA transfer—the migration of cells from person to person, and betwixt people and objects—is inevitable when nosotros touch, speak, exercise the laundry. A 1996 report showed that sperm cells from a single stain on 1 item of habiliment made their way onto every other item of clothing in the washer. And because we all shed different amounts of cells, the strongest Dna profile on an object doesn't always correspond to the person who virtually recently touched it. I could pick upwardly a knife at x in the morning, simply an analyst testing the handle that twenty-four hours might notice a stronger and more than complete Dna profile from my wife, who was using it four nights before. Or the analyst might find a profile of someone who never touched the knife at all. One recent written report asked participants to shake hands with a partner for two minutes and and then agree a pocketknife; when the DNA on the knives was analyzed, the partner was identified every bit a contributor in 85 pct of cases, and in 20 percentage as the main or sole contributor.

Given rates of transfer, the mere presence of DNA at a criminal offence scene shouldn't be enough for a prosecutor to obtain a conviction. Context is needed. What worries experts similar White potato is that advancements in Deoxyribonucleic acid testing are enabling ever more emphasis on e'er less substantial testify. A new technique known as depression-re-create-number analysis tin can derive a full DNA profile from every bit little equally ten trillionths of a gram of genetic material, by copying DNA fragments into a sample large plenty for testing. The technique non just carries a higher risk of sample contagion and allele dropout, but could likewise implicate someone who never came close to the criminal offense scene. Given the growing reliance on the codis database—which allows law to apply DNA samples to search for possible suspects, rather than only to verify the interest of existing suspects—the need to consider exculpatory evidence is greater than ever.

Simply Bicka Barlow, the San Francisco attorney, argues that the justice system at present allows picayune room for caution. Techs at many state-funded criminal offence labs have cops and prosecutors breathing downwardly their necks for results—cops and prosecutors who may work in the same edifice. The threat of bias is everywhere. "An analyst might be told, 'Okay, nosotros have a suspect. Hither's the Deoxyribonucleic acid. Look at the vaginal swab, and compare it to the suspect,' " Barlow says. "And they do, but they're also existence told all sorts of totally irrelevant things: The victim was 6 years old, the victim was traumatized, it was a hideous offense."

Indeed, some analysts are incentivized to produce inculpatory forensic testify: A recent study in the journal Criminal Justice Ethics notes that in North Carolina, state and local law-enforcement agencies operating offense labs are compensated $600 for DNA analysis that results in a confidence.

"I don't retrieve information technology'due south unreasonable to bespeak out that DNA testify is being used in a system that'south had horrible problems with evidentiary reliability," Tater, who worked for several years as a public defender, told me. No dependable estimates be for how many people accept been falsely accused or imprisoned on the basis of faulty DNA testify. But in Inside the Prison cell, she hints at the stakes: "The same broken criminal-justice system that created mass incarceration," she writes, "and that has candy millions through its mechanism without communicable even egregious instances of wrongful conviction, now has a new and powerful weapon in its arsenal."

The growing potential for mistakes in Dna testing has inspired a solution plumbing equipment for the digital age: automation, or the "complete removal of the man from doing whatever subjective conclusion making," as Marker Perlin, the CEO of the Dna-testing firm Cybergenetics, put it to me recently.

Perlin grew interested in DNA-typing techniques in the 1990s, while working equally a researcher on genome engineering science at Carnegie Mellon, and spent some time reviewing recent papers on forensic usage. He was "really disappointed" by what he found, he told me: Faced with complex Dna mixtures, analysts besides often arrived at flawed conclusions. An experienced coder, he set nearly designing software that could take some of the guesswork out of Dna profiling. Information technology could also process results much faster. In 1996, Perlin waved goodbye to his mail service at Carnegie Mellon, and together with his wife, Ria David, and a minor cadre of employees, focused on developing a programme they dubbed TrueAllele.

At the cadre of TrueAllele is an algorithm: Information from Deoxyribonucleic acid test strips are uploaded to a computer and run through an array of probability models until the software spits out a likelihood ratio—the probability, weighed confronting coincidence, that sample Ten is a friction match with sample Y. The idea, Perlin told me when I visited Cybergenetics headquarters, in Pittsburgh, was to correctly differentiate individual Deoxyribonucleic acid profiles found at the scene of a crime. He gave me an example: A lab submits data from a circuitous Deoxyribonucleic acid mixture found on a pocketknife used in a homicide. The TrueAllele system might conclude that a match betwixt the pocketknife and a doubtable is "five trillion times more probable than coincidence," and thus that the suspect almost certainly touched the knife. No more analysts squinting at their equipment, trying to correspond alleles with contributors. "Our program," Perlin told me proudly, "is able to do all that for you, more accurately."

Around us, half a dozen analysts and coders saturday hunched over computer screens. The office was windowless and devoid of any kind of ornament, save for a whiteboard laced with equations—the vibe was more bootstrapped first-up than CSI. "I retrieve visitors are surprised non to see bubbling vials and lab equipment," Perlin acknowledged. "Simply that's not us."

He led me downward the hallway and into a storage room. Row upon row of Cybergenetics-branded Apple desktop computers lined the shelves: prepare-made TrueAllele kits. Perlin could not tell me exactly how many software units he sells each year, only he allowed that TrueAllele had been purchased by crime labs in Oman, Australia, and 11 U.S. states; last year, Cybergenetics hired its showtime full-time salesman.

Four years ago, in one of its more than loftier-contour tests to engagement, the software was used to connect an extremely small-scale trace of Deoxyribonucleic acid at a murder scene in Schenectady, New York, to the killer, an acquaintance of the victim. A similarly reliable match, Perlin told me, would have been very hard to obtain past more analog ways.

And the software'due south potential is only starting to be mined, he added. TrueAllele'south ability to pull matches from microscopic or muddled traces of Deoxyribonucleic acid is helping crack cold cases, by reprocessing evidence one time dismissed as inconclusive. "Y'all hear the word inconclusive, you naturally recollect, Okay. It's done," Perlin told me, his eyes widening. "Merely it's not! It just means [the lab technicians] can't interpret information technology. Permit me ask you: What's the societal affect of half a law-breaking lab's prove beingness called inconclusive and prosecutors and police and defenders mistakenly assertive that this means it's uninformative information?"

His critics have a darker view. William Thompson points out that Perlin has declined to make public the algorithm that drives the plan. "You do have a blackness-box situation happening hither," Thompson told me. "The data become in, and out comes the solution, and nosotros're not fully informed of what happened in between."

Last year, at a murder trial in Pennsylvania where TrueAllele evidence had been introduced, defense attorneys demanded that Perlin turn over the source lawmaking for his software, noting that "without it, [the accused] will be unable to make up one's mind if TrueAllele does what Dr. Perlin claims it does." The gauge denied the request.

Only TrueAllele is just one of a number of "probabilistic genotyping" programs developed in recent years—and as the applied science has get more prominent, so as well have concerns that information technology could be replicating the problems information technology aims to solve. The Legal Aid Society of New York recently challenged a comparable software programme, the Forensic Statistical Tool, which was adult in-business firm by the city's Office of the Principal Medical Examiner. The FST had been used to test testify in hundreds of cases in the state, including an attempted-murder charge against a customer of Jessica Goldthwaite, a Legal Help attorney.

Goldthwaite knew lilliputian nigh DNA typing, merely one of her colleagues at the time, Susan Friedman, had earned a master'due south degree in biomedical science; another, Clinton Hughes, had been involved in several DNA cases. The iii attorneys decided to educate themselves about the technology, and questioned half a dozen scientists. The responses were emphatic: "I population geneticist we consulted said what the [medical examiner] had made public most the FST read more similar an ad than a scientific paper," Hughes told me. Another called information technology a "random number generator."

In 2011, Legal Assistance requested a hearing to question whether the software met the Frye standard of acceptance past the larger scientific customs. To Goldthwaite and her team, it seemed at to the lowest degree plausible that a relatively untested tool, especially in analyzing very small and degraded samples (the FST, similar TrueAllele, is sometimes used to analyze low-copy-number evidence), could exist turning up allele matches where at that place were none, or missing others that might have led technicians to an entirely different determination. And because the source code was kept secret, jurors couldn't know the actual likelihood of a faux match.

At the hearing, bolstered by a range of good testimony, Goldthwaite and her colleagues argued that the FST, far from existence established science, was an unknown quantity. (The medical examiner'due south office refused to provide Legal Assist with the details of its code; in the end, the team was compelled to reverse-engineer the algorithm to show its flaws.)

Judge Mark Dwyer agreed. "Judges are, far and away, not the people best qualified to explain scientific discipline," he began his decision. Still, he added, efforts to legitimize the methods "must go on, if they are to persuade." The FST evidence was ruled inadmissible.

Dwyer's ruling did non have the weight of precedent: Other courts are free to accept evidence analyzed past probabilistic software—more and more of which is likely to enter the courtroom in the coming years—as they come across fit. All the same, Goldthwaite told me, the fact that one judge had been willing to question the new science suggested that others might as well, and she and her team continue to file legal challenges.

When I interviewed Perlin at Cybergenetics headquarters, I raised the matter of transparency. He was visibly annoyed. He noted that he'd published detailed papers on the theory behind TrueAllele, and filed patent applications, too: "Nosotros take disclosed not the merchandise secrets of the source code or the applied science details, only the bones math."

To Perlin, much of the criticism is a case of sour grapes. "In any new development in forensic science, there's been incredible resistance to the idea that you're going to rely on a validated machine to give yous an authentic answer instead of relying on yourself and your expertise," he told me.

In 2012, shortly after Legal Aid filed its challenge to the FST, two developers in holland, Hinda Haned and Jeroen de Jong, released LRmix Studio, gratis and open-source Dna-profiling software—the lawmaking is publicly available for other users to explore and amend.

Erin Murphy, of NYU, has argued that if probabilistic Dna typing is to exist widely accustomed by the legal community—and she believes that i day it should exist—information technology will need to motility in this direction: toward transparency.

"The problem with all DNA profiling is that in that location isn't skepticism," she told me. "There isn't the necessary pressure level. Is at that place increasing recognition of the shortcomings of erstwhile-school applied science? Absolutely. Is there trepidation near the newer technology? Yes. Merely just because we're moving forrard doesn't mean mistakes aren't nevertheless being made."

On April 3, 2014, the Urban center of Houston shut downwardly its old crime lab and transferred all Deoxyribonucleic acid-testing operations to a new entity known as the Houston Forensic Science Center. Unlike its predecessor, which was overseen past the police department, the Forensic Science Centre is intended to be an democratic organization, with a firewall betwixt it and other branches of law enforcement. "I retrieve it's important for the forensic side to take that independence, and then nosotros tin can narrow information technology downward without worrying about which side is going to do good or profit from it, just narrowing it down to what we call back is the accurate information," Daniel Garner, the middle'due south head, told a local reporter.

And however Houston has been hard-pressed to leave its troubled history with forensic DNA backside. In June 2014, the Houston Relate reported that a former analyst at the one-time law-breaking lab, Peter Lentz, had resigned afterwards a Houston Police force Department internal investigation found evidence of misconduct, including improper procedure, lying, and tampering with an official record. A representative from the county district attorney's part told the Relate that her function was looking into all of the most 200 cases—including 51 murder cases—that Lentz had worked on during his time at the lab. (A thousand jury declined to indict Lentz for any wrongdoing; he could not exist reached for comment.)

"It'south almost 20 years later, and nosotros're still dealing with the repercussions," Josiah Sutton'south mother, Ballad Batie, told me earlier this year. "They say things are getting meliorate, and peradventure they are, but I ever answer that it wasn't fast plenty to salve Josiah."

Earlier entering prison, Batie said, Sutton had been a promising football player, with a college career ahead of him. After his exoneration, he seemed stuck in a land of suspended animation. He was angry and resentful of authority. He drifted from job to job. He received an initial lump-sum payment from the metropolis, as compensation for his wrongful conviction and the fourth dimension he spent in prison, forth with a much smaller monthly payout. But the lump-sum payment quickly vanished. He fathered five kids with v dissimilar women.

Batie called the urban center to ask about counseling for her son, just was told no such service was available. "I did my best to put myself in his shoes," Batie said. "I was annoyed, just I knew he felt like the world was against him. Anybody had ever given up on him. I couldn't give up on him besides."

Last summertime, Sutton was arrested for allegedly assaulting an acquaintance of his then-girlfriend. He spent the better office of a year in lockup earlier posting bail and is now awaiting trial. (Sutton denies the charges.) Batie believes that her son'due south issues are a directly outcome of his incarceration in 1999. "He had his childhood stolen from him," she told me. "No prom, no dating, no high-school graduation. Nothing. And he never recovered."

I wondered whether Batie blamed DNA. She laughed. "Oh, no, honey," she said. "DNA is science. You can't blame Dna. You tin only blame the people who used it wrong."

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/06/a-reasonable-doubt/480747/

0 Response to "Why Is There No Dna Reading for Me"

Post a Comment